Resisting Gentrification

2021

Client Personal project

Type Tactical urbanism

As a social worker engaged in academic discourse, much of the liberatory theory we discuss circulates only within closed academic circles and those with access to them. The social theories that unpack colonialism and oppression often are not shared with those who are most harmed by them. This project combinds graphic design, tactical urbanism, and direct action as a way to bring this discusion to these groups through creating opportunities for community members to express their existing experiential knowledge. I wrote the following essay to substantiate the utility of site specific design interventions in decolonizing places and the cocreation of knowledge.

I have been a member of the Ridgewood community for six years and have never felt more accepted by any neighborhood, including my rural hometown. My partner and I share a yard with three other units. The ground floor is occupied by a 50-year-old Puerto Rican guy, his young adult daughter, and her 7-year-old son. Their family has lived in the building for over 20 years, and the lore and traditions that accompany their tenure is extensive. Though we have very different ways of knowing and doing, we share a deep affection for our neighborhood and an appreciation for the mutual respect and support we have exchanged over the years. I am really honored we have made a small cameo in their family narrative. Still, my partner and I are part of a wave of young adults from predominately White, upper-middle class families who have been steadily moving to the area for the past decade, in search of inexpensive housing options. While neighborhood demographics naturally shift over time, our resettlement in the area represents a broader demographic shift that does not bode well for Ridgewood’s future.

Gentrification is a very literal, contemporary form of colonization. Property developers approach low-income neighborhoods the way Christian Europeans approached Indigenous land. Opportunistic, paternalistic, and profit driven: past and present colonizers view regions through a lens of what they could become and not what they already are. This framework fails to acknowledge the value of expertly constructed resource networks that have been built by and for the existing community. Not only do developers overlook the complexity of these systems, but they must also actively destroy them to make room for their own. As colonizers diminish the low-income residents’ ways of doing and knowing, so too do they underestimate their power.

Even in conversation with those who oppose community displacement, gentrification is frequently described as an inevitability of urban living. Before the condo renovations are completed and the wealthy, often White or White acculturated transplants are given their computerized key fobs, the neighborhood that was is already gone. At least this is the narrative we are taught to accept. Our belief in the manifest destiny of gentrification is coloniality at work and it is how American systems of power and hegemony are maintained (hooks, 1994). Accepting that low-income residents must choose between assimilation or displacement fails to capitalize on their historic ingenuity or adequately value their significant experiential knowledge.

The Ridgewood Tenets Union (RTU) is a local community organization that formally resists the gentrification of the neighborhood through community outreach programing. They have successfully installed community refrigerators throughout the neighborhood and have organized public demonstrations that seek to educate local residents on gentrification, coloniality, and white supremacy. I have attended a few of these formal resistance efforts and was disappointed—though unsurprised—to find the vast majority of participants to be like me: neighborhood transplants who were young, educated, and predominantly White. My discomfort was crystalized during the Summer 2020, when I joined a Black Lives Matter march organized by RTU. I found myself walking beside a White woman with a megaphone who was leading a call and response chant of “Whose streets? Our streets”. Not only was her use of the megaphone literally tone deaf in the context of a march specifically meant to center Black voices, but it also was abundantly clear to me that the streets we were dominating did not, in fact, belong to us.

Though Ridgewood natives don’t generally attend these events for one or many possible reasons—lack of awareness, busy schedules, and/or feeling generally unwelcome—the most important take away is that they don’t. Though RTU’s efforts to educate, inspire, and agitate the community are in good faith, they fail to reach those who might stand to benefit most from a unified front of resistance.

When asked to make a contribution to the decolonization of social work practice, I decided I would not write an academic paper. In Teaching to Transgress, bell hooks wrote that we are “revolutionaries in the abstract but not in our daily lives.” Rather than creating and disseminating knowledge within the limited pool of academia I am privileged to have access, I became increasingly interested in engaging my community in a dialogue that would hopefully lead to the dissemination of their cumulative experiential knowledge, not mine alone. Though I have an abundance of respect for RTU and the contributions they have made to the preservation of the Ridgewood neighborhood, some of their community interventions have felt reminiscent of social work’s colonial origins. Rather than engaging the broader community on their terms, RTU inadvertently places the burden of service discovery and utilization on the individuals.

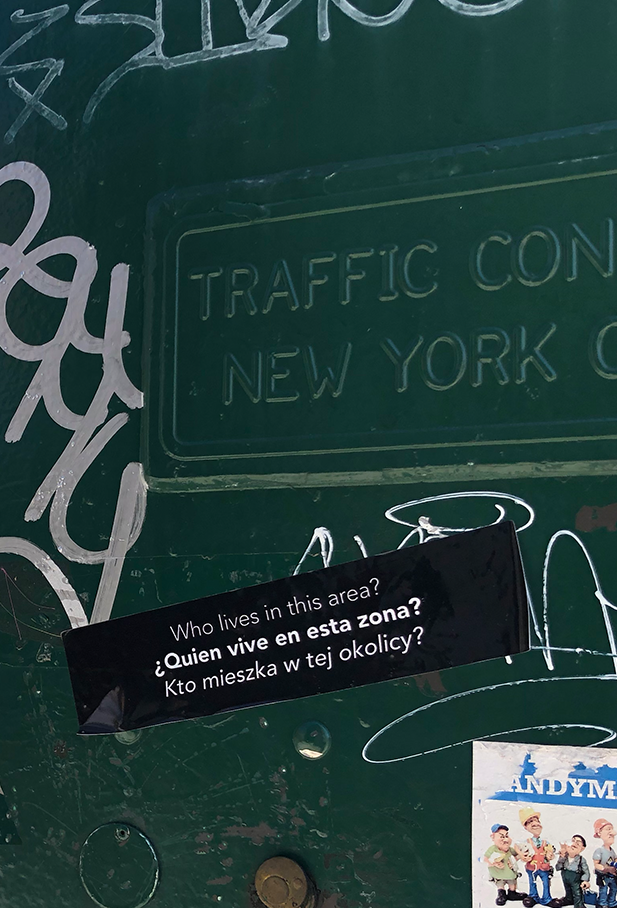

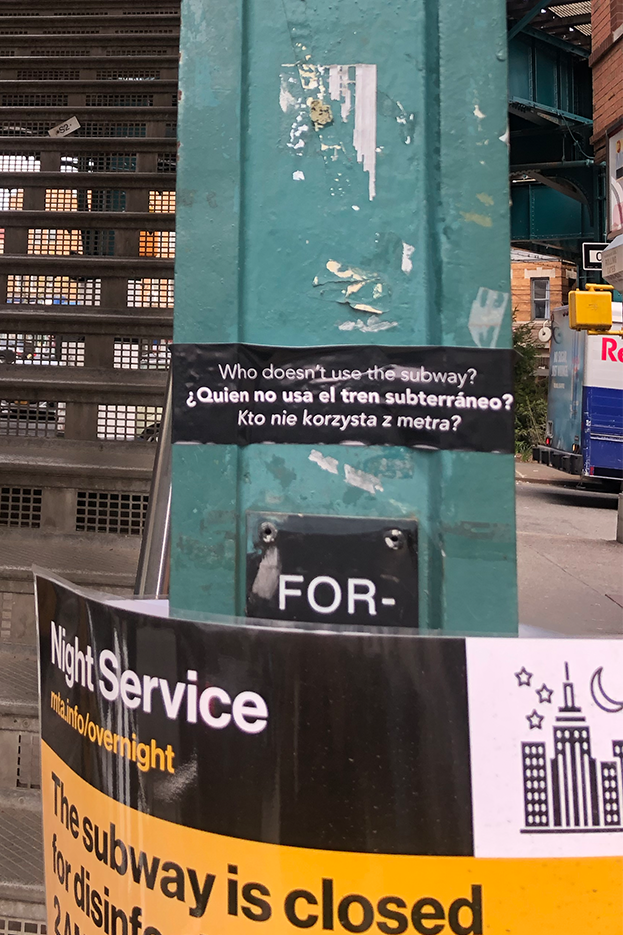

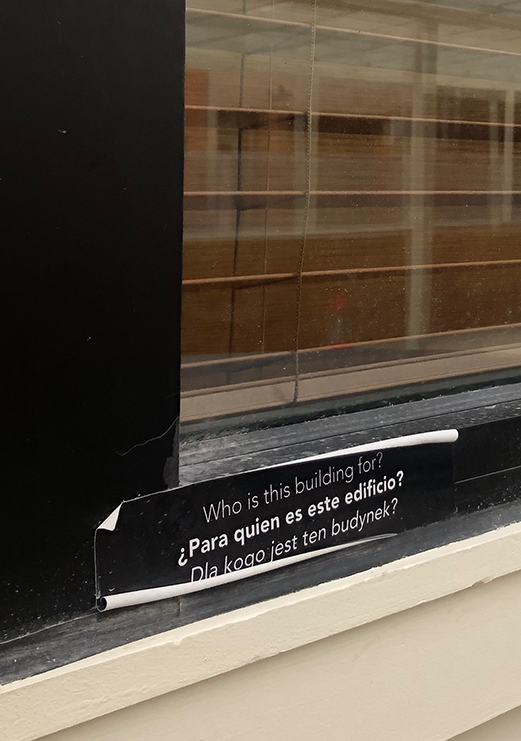

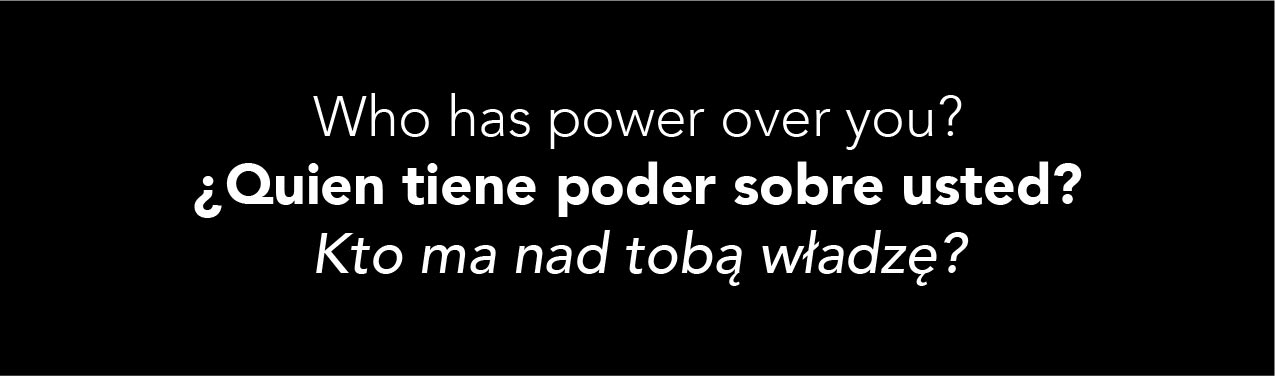

Inspired by from Brazilian educator Paolo Friere’s proposition that colonial power structures can be dismantled through actively critiquing environments, I set about drafting six questions that would engage native Ridgewood residents in an optional dialogue. These are the prompts I settled on:

Who lives in this area?

Who has power over you?

Who is this building for?

Who doesn’t use the subway?

Where do you feel unwelcome?

Who uses the sidewalk?

I printed these questions on stickers at a local shop and placed them throughout the neighborhood on fire hydrants, telephone poles, subway stations, and new upscale developments. Not only are the questions written in English, they are also written in Spanish and Polish and comply with ADA accessibility guidelines. In its recently history, the predominant working-class, ethnic minorities who reside in Ridgewood are Polish and Puerto Ricans. The questions are positioned for maximum visibility, in and below the average adult’s line of sight so pedestrians can interact with them as they use the sidewalk. Their placement also intentionally calls attention to infrastructure that is potentially oppressive. Rather than proposing these questions in a formal setting where participants may feel put upon to give an answer, they are asked in the absence of a beneficiary beyond the viewer. Not only does this imbue community members with the power to choose how they interact with the prompts, it actively values their consideration as a private, important event.

I don’t believe any of these questions will be unfamiliar to the residents who will encounter them. My intention is not to impose my ways of knowing and doing onto others, but to ask questions that may facilitate the expression of knowledge my community already possess, whose conjuring may challenge the manifest destiny hegemony surrounding gentrification (hooks, 1994).

When I set out to document the stickers, I encountered two residents actively engaging in an intense dialogue directly in front of my sticker. A Hassidic man and non-Hassidic woman stood facing the glass façade of an unfilled condominium, where I had placed, “Who is this building for?” I sat somewhat conspicuously nearby to eavesdrop, to determine if this was a coincidence or an actual example of my intervention at work. Unbelievably, just 12 hours after they had been posted, I overheard a local resident explain to a landlord the way gentrification destroys local education. I hope these tiny interventions can continue to inspire similar dialogues that might contribute to the preservation of a community that has given me more than I can realistically hope to reciprocate.

The Ridgewood Tenets Union (RTU) is a local community organization that formally resists the gentrification of the neighborhood through community outreach programing. They have successfully installed community refrigerators throughout the neighborhood and have organized public demonstrations that seek to educate local residents on gentrification, coloniality, and white supremacy. I have attended a few of these formal resistance efforts and was disappointed—though unsurprised—to find the vast majority of participants to be like me: neighborhood transplants who were young, educated, and predominantly White. My discomfort was crystalized during the Summer 2020, when I joined a Black Lives Matter march organized by RTU. I found myself walking beside a White woman with a megaphone who was leading a call and response chant of “Whose streets? Our streets”. Not only was her use of the megaphone literally tone deaf in the context of a march specifically meant to center Black voices, but it also was abundantly clear to me that the streets we were dominating did not, in fact, belong to us.

Though Ridgewood natives don’t generally attend these events for one or many possible reasons—lack of awareness, busy schedules, and/or feeling generally unwelcome—the most important take away is that they don’t. Though RTU’s efforts to educate, inspire, and agitate the community are in good faith, they fail to reach those who might stand to benefit most from a unified front of resistance.

When asked to make a contribution to the decolonization of social work practice, I decided I would not write an academic paper. In Teaching to Transgress, bell hooks wrote that we are “revolutionaries in the abstract but not in our daily lives.” Rather than creating and disseminating knowledge within the limited pool of academia I am privileged to have access, I became increasingly interested in engaging my community in a dialogue that would hopefully lead to the dissemination of their cumulative experiential knowledge, not mine alone. Though I have an abundance of respect for RTU and the contributions they have made to the preservation of the Ridgewood neighborhood, some of their community interventions have felt reminiscent of social work’s colonial origins. Rather than engaging the broader community on their terms, RTU inadvertently places the burden of service discovery and utilization on the individuals.

Inspired by from Brazilian educator Paolo Friere’s proposition that colonial power structures can be dismantled through actively critiquing environments, I set about drafting six questions that would engage native Ridgewood residents in an optional dialogue. These are the prompts I settled on:

Who lives in this area?

Who has power over you?

Who is this building for?

Who doesn’t use the subway?

Where do you feel unwelcome?

Who uses the sidewalk?

I printed these questions on stickers at a local shop and placed them throughout the neighborhood on fire hydrants, telephone poles, subway stations, and new upscale developments. Not only are the questions written in English, they are also written in Spanish and Polish and comply with ADA accessibility guidelines. In its recently history, the predominant working-class, ethnic minorities who reside in Ridgewood are Polish and Puerto Ricans. The questions are positioned for maximum visibility, in and below the average adult’s line of sight so pedestrians can interact with them as they use the sidewalk. Their placement also intentionally calls attention to infrastructure that is potentially oppressive. Rather than proposing these questions in a formal setting where participants may feel put upon to give an answer, they are asked in the absence of a beneficiary beyond the viewer. Not only does this imbue community members with the power to choose how they interact with the prompts, it actively values their consideration as a private, important event.

I don’t believe any of these questions will be unfamiliar to the residents who will encounter them. My intention is not to impose my ways of knowing and doing onto others, but to ask questions that may facilitate the expression of knowledge my community already possess, whose conjuring may challenge the manifest destiny hegemony surrounding gentrification (hooks, 1994).

When I set out to document the stickers, I encountered two residents actively engaging in an intense dialogue directly in front of my sticker. A Hassidic man and non-Hassidic woman stood facing the glass façade of an unfilled condominium, where I had placed, “Who is this building for?” I sat somewhat conspicuously nearby to eavesdrop, to determine if this was a coincidence or an actual example of my intervention at work. Unbelievably, just 12 hours after they had been posted, I overheard a local resident explain to a landlord the way gentrification destroys local education. I hope these tiny interventions can continue to inspire similar dialogues that might contribute to the preservation of a community that has given me more than I can realistically hope to reciprocate.